Does price floor works?

A price floor is a minimum price allowed by law. That is, it is a price below which it is illegal to buy or sell, called a price floor because you cannot go below the floor. We're going to show that price floors create four significant effects: surpluses, lost gains from trade, wasteful increases in quality, and a misallocation of resources.

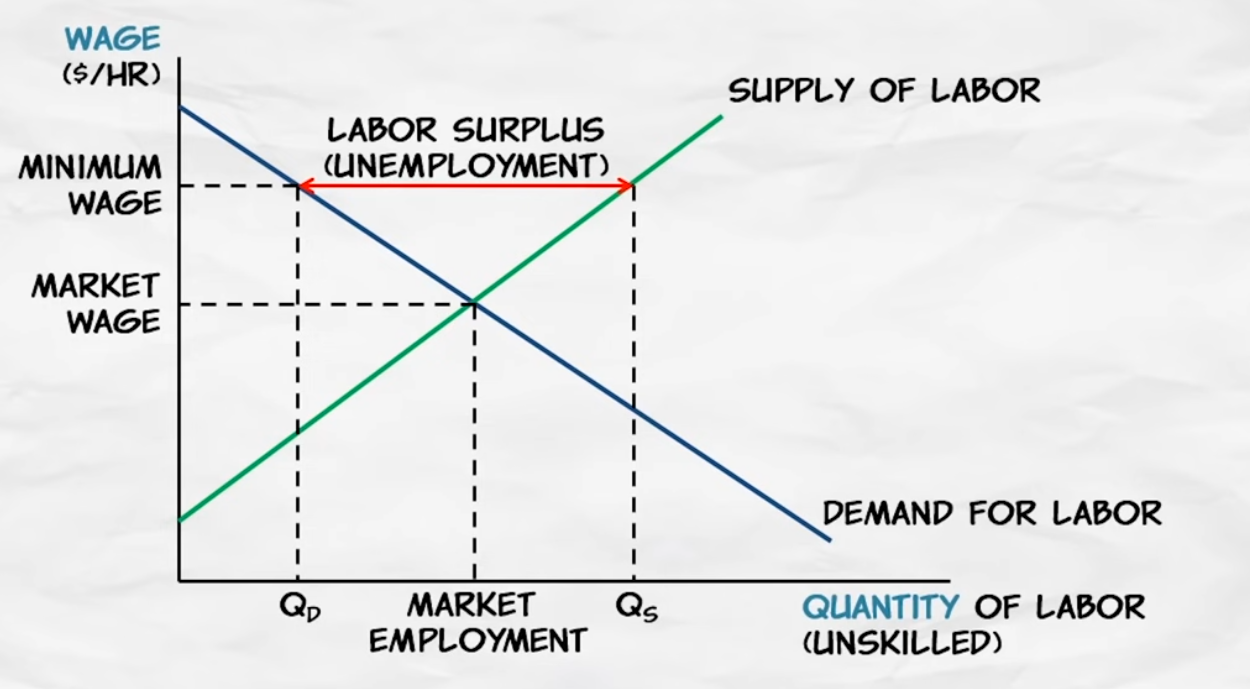

What is surplus of labor with mininum wage? Unemployment

The minimum wage is a price floor, so it's going to create a surplus. A surplus of labor, we call what? A surplus of labor is called unemployment.

Now, who will the minimum wage affect?

Now, who will the minimum wage affect? Workers with very high productivity who are already earning more than the minimum wage – they are not going to be affected by the minimum wage perhaps at all. Instead, it will affect the least experienced, least educated, least trained workers. Low-skilled teenagers, for example, are most likely to be affected by the minimum wage.

Modest increase in minimum wage

Now the minimum wage is a controversial and hotly debated issue. Some academic results indicate that the unemployment effect of a modest increase in the minimum wage would not be substantial. At the same time, however, we also have to recognize that a modest increase in the minimum wage would not have big benefits either. First, only a small percentage of workers are going to be affected by the minimum wage. 97% or so of workers already earn more than the minimum wage.

Large increase in the minimum wage

So a large increase in the minimum wage is going to cause serious unemployment, and the good example of this is Puerto Rico in 1938. Congress actually set the first minimum wage at this time at 25 cents an hour. Now that may seem low, but that's at a time when the average wage in the United States was still less than a dollar an hour, was 62 and a half cents an hour. Congress, however, forgot to exempt Puerto Rico, when the average wages in Puerto Rico at that time were much lower than in the rest of the United States, only three cents to four cents an hour. And lots of Puerto Rican firms went bankrupt, it created devastating unemployment. In fact, Puerto Rican politicians came to Washington to beg for an exemption to get them out of the minimum wage. So, a large increase in the minimum wage would certainly cause substantial and serious unemployment.

We do see higher minimum wages in other countries. The minimum wage in France is higher than the U.S., relative to average wages in those two countries. In addition, labor laws in France make it very difficult to fire workers once they have been hired. As a result, firms in France are very reluctant to hire new workers.

Younger workers are especially affected because they are less productive, and also they are less known commodities. So, the risk of hiring them is greater. As a result, unemployment among young workers is very high in France. It was 23% in 2005, and that was long before the economic crisis, the financial crisis affecting the entire world. So even during good times, unemployment in France among young workers is very high, because the minimum wage is high, and because firms don't want to hire, given how difficult it is to fire workers.

Why do governments enact price controls?

So far, we've looked at a number of the consequences of price controls, both price ceilings and price floors. And most of the consequences, they're not very good.i

Public simply did not connect wage and price controls with their consequences

In November of 1972, Nixon won re-election in a landslide. So, wage and price controls were popular. Nixon was re-elected with this policy as well as with others. Now, why is this? I think in many cases, in a majority of cases, the public simply did not connect wage and price controls with their consequences. So, looking around and the shortages, the long line-ups for gasoline, they didn't say the cause of that is the price control.

Price floor in agriculture

Price floors are also used often in agriculture to try to protect farmers.

As you might have guessed, this creates a problem. There is less quantity demanded (consumed) than quantity supplied (produced). This is called a surplus. If the surplus is allowed to be in the market then the price would actually drop below the equilibrium. In order to prevent this the government must step in. The government has a few options:

-

They can buy up all the surplus. For a while the US government bought grain surpluses in the US and then gave all the grain to Africa. This might have been nice for African consumers, but it destroyed African farmers.

-

They can strictly enforce the price floor and let the surplus go to waste. This means that the suppliers that are able to sell their goods are better off while those who can't sell theirs (because of lack of demand) will be worse off. Minimum wage laws, for example, mean that some workers who are willing to work at a lower wage don't get to work at all. Such workers make up a portion of the unemployed (this is called "structural unemployment").

-

The government can control how much is produced. To prevent too many suppliers from producing, the government can give out production rights or pay people not to produce. Giving out production rights will lead to lobbying for the lucrative rights or even bribery. If the government pays people not to produce, then suddenly more producers will show up and ask to be payed.

-

They can also subsidize consumption. To get demanders to purchase more of the surplus, the government can pay part of the costs. This would obviously get expensive really fast.

Implementing MSP in India

In India, 6.7 million children are going without food, and the question is whether a price floor can still create a surplus. Surplus occurs not because there are not enough people who need the product, but because enough people fail to purchase it at a particular price. At a price floor, there will be far more people who fail to purchase it as the quantity supplied exceeds the quantity demanded, as shown in the diagram.

So price floor is a bad idea. In what way we can protect farmers?

Todo!

Anthelmintic Drug

Albendazole

https://reference.medscape.com/drug/albenza-albendazole-342648

Single-dose oral albendazole is more efficacious against hookworm than mebendazole. To achieve high CRs against both hookworm and T. trichiura, triple-dose regimens are warranted.

After giving a single dose of albendazole 400 mg to 37 people who were positive for Ascaris lumbricoides, 37 people had not found eggs of Ascaris lumbricoides on faecal examination after treatment. Positive subjects Trichuris trichiura were 54 people (mild infections 51.85%, moderate infections 44.44% and severe infections 3.73%). After giving a single dose of albendazole 400 mg to 54 positive people Trichuris trichiura, in severe infections, the percentage of eggs dropped was 100%. In moderate infections, the percentage of the number of eggs dropped is 95.83%. In mild infections, the percentage of total recovery was 7.14%, and the percentage of eggs dropped was 39.29%.

Albendazole, an effective single dose, broad spectrum anthelmintic drug

Albendazole, a new anthelmintic drug was evaluated in Malaysia in 91 patients, with single or mixed infections of Ascaris, Trichuris, and hookworm. Albendazole was administered as a single dose of 400 mg, 600 mg, or 800 mg. The cure rate for Ascaris at all three doses was 100% at days 14 and 21 post-treatment; for hookworm it was 98.8%, 100% and 98%, respectively, at day 14 and 68.8%, 100% and 84%, respectively, at day 21; for Trichuris it was 31.2%, 57.1% and 42.3%, respectively, at day 14 and 27.3%, 60.9% and 48.0%, respectively, at day 21. The egg reduction rate at day 21 was 100% at all three doses for Ascaris, 94.5%, 100% and 96.1%, respectively, for hookworm; and 39.2%, 85.1% and 72.8%, respectively, for Trichuris. There were no side effects, and biochemical examination of blood and urine did not indicate any unfavourable changes. Based on this trial, the recommended dosage for Ascaris and hookworm is a 400 mg single dose, and for Trichuris is a 600 mg single dose. Albendazole appears to be more effective than other available anthelmintic drugs.

Homeopathy Draft

Homeopathy or homoeopathy is a pseudoscientific system of alternative medicine.

- Explain Pseudoscience

Pseudoscience consists of statements, beliefs, or practices that claim to be both scientific and factual but are incompatible with the scientific method.

- Scientific method

- Alternative medicine

- Blinded experiment

- Placebo effect

- Body immune system

- Preparation of Homeopathy

- Dilution of homeopathy

- Composition of some real homeopathy medicine

- Efficacy of homeopathy

- Arguments of common people about homeopathy

- Govt policies and funding on homeopathy

Prescribing an antibiotic? Pair it with probiotics

https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC3601687/

When you prescribe antibiotics, tell patients that taking probiotics for the entire course of treatment will help prevent diarrhea.

PRACTICE CHANGER

Recommend that patients taking antibiotics also take probiotics, which have been found to be effective both for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea (AAD).1

STRENGTH OF RECOMMENDATION

A: Based on a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.

Hempel S, Newberry S, Maher A, et al. Probiotics for the prevention and treatment of antibiotic-associated diarrhea. JAMA. 2012;307: 1959-1969.

ILLUSTRATIVE CASE

When you prescribe an antibiotic for a 45-year-old patient with Helicobacter pylori, he worries that the medication will cause diarrhea. Should you recommend that he take probiotics?

More than a third of patients taking antibiotics develop AAD, and in 17% of cases, AAD is fatal. Although the diarrhea may be the result of increased gastrointestinal (GI) motility in some cases, a disruption of the GI flora that normally acts as a barrier to infection and aids in the digestion of carbohydrates is a far more common cause.

Helicobacter Pylori

23 years of the discovery of Helicobacter pylori: Is the debate over?

Situation is exactly opposite in many of the developing countries

Helicobacter pylori is a bacterium that colonizes human stomach and is an established cause of chronic superficial gastritis, chronic active gastritis, peptic ulcer disease and gastric adenocarcinoma. The infection is on a fast decline in most of the western countries, mainly due to the success of therapeutic regimens and improved personal and community hygiene that prevents re-infection. The eradication in some of the countries has been quite promising and the pathogen was declared as an endangered bacterial species. However, the situation is exactly opposite in many of the developing countries due to failure of treatment and emergence of drug resistance.

H. pylori is the primary cause of peptic ulcers and gastric cancer

The prevalence of H. pylori infection remains high (> 50%) in much of the world, although the infection rates are dropping in some developed nations

Beyond the stomach: An updated view of Helicobacter pylori pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment

Helicobacter pylori (H. pylori) is an extremely common, yet underappreciated, pathogen that is able to alter host physiology and subvert the host immune response, allowing it to persist for the life of the host. H. pylori is the primary cause of peptic ulcers and gastric cancer. In the United States, the annual cost associated with peptic ulcer disease is estimated to be $6 billion and gastric cancer kills over 700000 people per year globally. The prevalence of H. pylori infection remains high (> 50%) in much of the world, although the infection rates are dropping in some developed nations. The drop in H. pylori prevalence could be a double-edged sword, reducing the incidence of gastric diseases while increasing the risk of allergies and esophageal diseases. The list of diseases potentially caused by H. pylori continues to grow; however, mechanistic explanations of how H. pylori could contribute to extragastric diseases lag far behind clinical studies. A number of host factors and H. pylori virulence factors act in concert to determine which individuals are at the highest risk of disease. These include bacterial cytotoxins and polymorphisms in host genes responsible for directing the immune response. This review discusses the latest advances in H. pylori pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Up-to-date information on correlations between H. pylori and extragastric diseases is also provided.

Fatty Liver

Experts warn of fatty liver disease 'epidemic' in young people

Nonalcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) is emerging as an important cause of liver disease in India. Epidemiological studies suggest prevalence of NAFLD in around 9% to 32% of general population in India with higher prevalence in those with overweight or obesity and those with diabetes or prediabetes.

Treatment of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease

Causes of non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease

Non‐alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD) occurs across all age groups and ethnicities and is recognised to occur in 14%–30% of the general population. Primary NAFLD is related to insulin resistance and thus frequently occurs as part of the metabolic changes that accompany obesity, diabetes, and hyperlipidaemia.

| Primary | Obesity, glucose intolerance, hypertriglyceridaemia, low HDL cholesterol, hypertension |

| Nutritional | Protein‐calorie malnutrition, rapid weight loss, gastrointestinal bypass surgery, total parental nutrition |

| Drugs | Glucocorticoids, oestrogens, tamoxifen, amiodarone, methotrexate, diltiazem, zidovudine, valproate, aspirin, tetracycline, cocaine |

| Metabolic | Lipodystrophy, hypopituitarism, dysbetalipoproteinaemia, Weber‐Christian disease |

| Toxins | Amanita phalloides mushroom, phosphorus poisoning, petrochemicals, bacillus cereus toxin |

| Infections | Human immunodeficiency virus, hepatitis C, small bowel diverticulosis with bacterial overgrowth |

Treatment strategies

Treatment strategies for NAFLD have revolved around (1) identification and treatment of associated metabolic conditions such as diabetes and hyperlipidaemia; (2) improving insulin resistance by weight loss, exercise, or pharmacotherapy; (3) using hepato‐protective agents such as antioxidants to protect the liver from secondary insults

Baby Parenting

Updates here:

https://iambrainstorming.github.io/chapters/parenting/baby_parenting.html

Amount and Schedule of Baby Formula Feeding

From American Academy of Pediatrics

On average, your baby should take in about 2½ ounces (75 mL) of infant formula a day for every pound (453 g) of body weight.

Amount and Schedule of Baby Formula Feedings

How Much and How Often Should a Newborn Drink Breast Milk?

How Much Formula Should a Newborn Eat?

How to Calm a Fussy Baby

How to Calm a Fussy Baby: Tips for Parents & Caregivers

Checklist for what your baby may need:

Here are some other reasons why your baby may cry and tips on what you can try to meet that need. If your baby is…

Hungry.

Keep track of feeding times and look for early signs of hunger, such as lip-smacking or moving fists to his mouth.

Cold or hot.

Dress your baby in about the same layers of clothing that you are wearing to be comfortable.

Wet or soiled.

Check the diaper. In the first few months, babies wet and soil their diapers a lot.

Spitting up or vomiting a lot.

Some babies have symptoms from gastroesophageal reflux (GER), and the fussiness can be confused with colic. Contact your child's doctor if your baby is fussy after feeding, has excessive spitting or vomiting, and is losing or not gaining weight.

Sick (has a fever or other illness).

Check your baby's temperature. If your baby is younger than 2 months and has a fever, call your child's doctor right away. See Fever and Your Baby for more information.

Overstimulated.

Try ways to calm your baby mentioned above.

Bored.

Quietly sing or hum a song to your baby. Go for a walk.

Baby should never be shaken

No matter how impatient or angry you become, a baby should never be shaken. Shaking an infant hard can cause blindness, brain damage or even death

The Baby Poop and Urination Guide

The Baby Poop Guide: What's Normal and What's Not

The short answer is baby poop that has a green, mustard yellow, or brown color and is soft and grainy is completely normal, but poop that has a white, red, or black color is not.

Breastfed baby poop frequency

According to Dr. Pittman, it can be normal for a breastfed baby to have one bowel movement each week—but it's also normal for them to poop after every feeding. (In other words, as long as a breastfed baby is pooping at least once a week, you're probably good.)

Formula-fed baby poop frequency

Formula-fed baby poop is usually different than breastfed baby poop. That's because stool moves through the intestines more slowly with formula, causing babies to go about once or twice per day, every one or two days, after the first couple of months. Note, however, that some formula-fed infants will poop up to three or four times daily at first.

Here's How Many Wet Diapers a Newborn Should Have

Here's How Many Wet Diapers a Newborn Should Have

Breastfeeding

Breast milk is widely recognized as the optimal source of nutrition for infants, providing essential nutrients, antibodies, and hormones that foster healthy growth and development. The American Academy of Pediatrics recommends exclusive breastfeeding for the first six months of life, citing numerous benefits including enhanced cognitive development, boosted immune systems, and a reduced risk of respiratory and ear infections.

Breast Pumping

However, for mothers who have undergone a cesarean section or those who must return to work, breastfeeding can be a challenge. In such cases, breastpumping milk can be an efficient way to feed breast milk to baby through a bottle, ensuring that they still receive the benefits of breast milk even when direct breastfeeding is not possible. By expressing milk and storing it in a bottle, mothers can maintain their milk supply, alleviate engorgement, and provide their baby with the nourishment they need, even when they are not physically present. This approach also allows partners, caregivers, or family members to participate in feeding, making it a convenient and practical solution for modern families.

Mother's Health and Breast feeding

Breastfeeding has health benefits for the mother too! Breastfeeding can reduce the mother's risk of breast and ovarian cancer, type 2 diabetes, and high blood pressure.

Exclusive breastfeeding for optimal growth, development and health of infantsi

Five great benefits of breastfeeding

Exclusive breastfeeding for about the first six months is recommended. The Dietary Guidelines for Americans recommends continued breastfeeding while introducing appropriate complementary foods until children are 12 months old or older.

The American Academy of Pediatrics and the World Health Organization also recommend exclusive breastfeeding for about 6 months, with continued breastfeeding along with introducing appropriate complementary foods for up to 2 years of age or longer.

Consistency vs Procrastination

Consistency in dedicating time each day to learning something new is essential for several reasons. Firstly, regular practice reinforces memory and aids in retaining information. When you engage with new material daily, the repetition helps to solidify your understanding, making it easier to recall and apply the knowledge in various contexts. This continuous engagement also builds momentum, making the learning process more fluid and less overwhelming. By establishing a daily routine, you create a habit that integrates learning seamlessly into your life, ensuring steady progress over time.

Furthermore, daily learning fosters a sense of discipline and commitment. It encourages you to set aside distractions and focus on your growth and development. This consistent effort can lead to significant improvements in skills and knowledge, which are often necessary for personal and professional advancement. Moreover, regular learning keeps your mind active and engaged, promoting cognitive health and potentially staving off mental decline as you age. It helps you stay curious, adaptable, and open to new ideas, which are crucial traits in an ever-changing world.

On the other hand, procrastination can have several negative consequences. When you delay learning or putting effort into acquiring new skills, you miss out on opportunities for growth and development. Procrastination often leads to a rush to meet deadlines or cram information at the last minute, resulting in a superficial understanding rather than deep, meaningful learning. This haphazard approach can cause stress and anxiety, reducing the overall enjoyment and effectiveness of the learning process.

Additionally, procrastination can create a cycle of guilt and decreased motivation. The more you put off tasks, the more daunting they seem, leading to a buildup of unfinished work and unachieved goals. This can erode your self-confidence and create a negative self-perception. Over time, habitual procrastination can hinder personal and professional achievements, limiting your potential and impacting your overall well-being. By recognizing the importance of consistency and actively working to overcome procrastination, you can cultivate a more productive and fulfilling approach to learning and personal growth.

Slow and steady wins the race

Complex subjects often require a deep understanding and the ability to integrate various concepts, which cannot be achieved through rushed or sporadic efforts. By approaching learning in a slow and steady manner, you give yourself the time needed to thoroughly grasp each component of the material.

Learning complicated material gradually allows for the accumulation of knowledge in manageable increments. This method reduces the cognitive load and prevents the feeling of being overwhelmed, which can often occur when trying to absorb too much information at once. Breaking down the material into smaller, more digestible parts and consistently working through them each day enables a more profound comprehension and retention of the subject matter. This approach mirrors the fable of the tortoise and the hare, where the consistent, patient efforts of the tortoise ultimately lead to success.

Moreover, slow and steady learning helps in building a strong foundation. Complicated subjects typically build upon basic principles. By taking the time to master these foundational elements thoroughly, you create a solid base upon which more advanced concepts can be understood more easily. This methodical progression ensures that gaps in knowledge are identified and addressed promptly, preventing future misunderstandings or the need for relearning.

In contrast, attempting to rush through complicated material can lead to superficial learning. This approach often results in a fragile understanding that can easily collapse under the weight of more advanced topics. Procrastination and cramming might yield short-term results, such as passing an exam, but they do not foster long-term retention or the ability to apply knowledge effectively. Therefore, adopting a "slow and steady" approach is not only more sustainable but also more effective in achieving true mastery of complicated subjects.

Consistency in exercise

Consistency in exercise, much like in learning, plays a crucial role in achieving long-term benefits and forming healthy habits. Regular physical activity, performed consistently over time, leads to significant improvements in physical health, such as increased strength, endurance, and flexibility. Establishing a daily exercise routine fosters discipline and creates a positive feedback loop; the more consistently you exercise, the more likely you are to continue, reinforcing the habit. This regularity is key to reaping the full benefits of exercise, which go beyond just physical health and extend to mental well-being and cognitive functioning.

Procrastination in exercise, on the other hand, can have numerous negative consequences. Delaying physical activity often leads to a sedentary lifestyle, which is associated with various health issues, including obesity, cardiovascular diseases, and weakened muscles. Procrastination can also result in inconsistent workout patterns, making it harder to see progress and stay motivated. The lack of a regular exercise routine can lead to feelings of guilt and decreased self-esteem, further discouraging you from engaging in physical activity.

The benefits of consistent exercise on mental well-being are well-documented. Regular physical activity releases endorphins, the body's natural mood elevators, which can reduce feelings of stress, anxiety, and depression. Exercise also promotes better sleep, which is essential for overall mental health. Engaging in physical activity can enhance cognitive functions such as memory, attention, and problem-solving skills. This is because exercise increases blood flow to the brain, promoting the growth of new neurons and improving brain plasticity, which is vital for learning and adapting to new information.

Moreover, exercise has been shown to improve focus and concentration, which are crucial for effective learning. Regular physical activity can boost your energy levels and reduce fatigue, making it easier to stay engaged and motivated when studying or learning new material. The discipline and routine developed through consistent exercise can also translate to other areas of life, including academics and professional pursuits. This disciplined approach helps to build resilience and the ability to tackle complex tasks with a clear and focused mind.

Exercise

Reduces Stress and Anxiety

Exercise helps calm the mind and body, reducing feelings of stress and anxiety by slowing down your heart rate and promoting relaxation.

Improves Oxygenation

Exercise increases oxygen levels in the body, which can improve cognitive function, boost energy, and support overall health.

Lowers Blood Pressure

Regular exercises have been shown to lower blood pressure and reduce the risk of heart disease.

Enhances Sleep

Exercise can help improve sleep quality by relaxing the body and mind, making it easier to fall asleep and stay asleep.

Increases Focus and Concentration

Exercises can improve attention and focus by reducing mind-wandering and increasing mental clarity.

Boosts Immune System

Habitual exercise improves immune regulation, delaying the onset of age-related dysfunction.

Reduces Migraine

Strength training exercise regimens demonstrated the highest efficacy in reducing migraine burden, followed by high-intensity aerobic exercise.

Improves Digestion

Deep breathing can help stimulate digestion, reduce symptoms of irritable bowel syndrome (IBS), and promote a healthy gut microbiome.

Increases Self-Awareness

Exercises can help increase self-awareness, allowing you to better understand your thoughts, emotions, and behaviors.

Supports Emotional Well-being

Exercises can help reduce symptoms of depression and anxiety, promoting emotional balance and well-being.

Improves Athletic Performance

Exercises can improve endurance, reduce fatigue, and enhance overall athletic performance.

Reduces Inflammation

Exercises has anti-inflammatory effects, which can help reduce inflammation and promote overall health.

Supports Weight Loss

Exercises can help reduce stress-related eating and increase feelings of fullness, supporting weight loss efforts.

Improves Respiratory Function

Exercises can improve lung function, increase oxygen capacity, and reduce symptoms of respiratory conditions like asthma.

Increases Mindfulness

Exercises promote mindfulness, encouraging you to focus on the present moment and let go of worries about the past or future.

Overall, incorporating exercises into your daily routine can have a profound impact on both physical and mental health, leading to a greater sense of well-being and overall quality of life.

Linux cheat sheet

https://www.stationx.net/linux-command-line-cheat-sheet/

Paths to Peace and Conflict: From the Body to the International

Non-State Actors and International Relations

In international relations, the traditional focus is on sovereign states. Through time, the discipline has also recognized the importance of international organizations, multinational corporations and civil society. The latter have, however, been more marginal in the study of peace and security but have gained increasing attention, most significantly after the terrorist attacks on the U.S. on September 11, 2001. With that shift in focus. We have a tendency to think of non-state actors as negative, which they certainly can be. But there are also positive actors in many ways, with non-governmental organizations and other civil society actors playing a significant role in the resolution of conflict and in peacebuilding in many regions of the world. In this class, we're looking at different types of non-state actors. In the field of international relations, the state has been the dominant actor and focus of attention. We assume that states are coherent actors with authority over both defined territory and the use of force. The inverse is then assumed to be true of non-state actors. They are not perceived as cohesive actors, and they are assumed not to have authority over either defined territory or a population. Nor are they thought of as commanding monopoly of the use of force. And this is despite the fact that in many parts of the world, particularly ones that are in conflict, the state is often unable to provide security to its citizens. And as feminist scholars have often noted, the state is actually often what undermines security. And here it is also important to remember that feminists do not see the state as being monolithic because gendered lenses show us that people are actors, the system has multiple hierarchies and it is characterized by multiple relations as Joshua Goldstein has argued. The state's inability to provide security requires us to think of non-state actors as relevant and peacebuilding, and we must have an open mind to the different types of non-state actors. These can include non-governmental organizations, charities, faith based groups, lobby groups, multinational corporations, diasporas and organized ethnic groups, even celebrities, most of whom would be considered positive actors. The negative actors, however, include organized criminal organizations and terrorist groups, which are often opaque and thus difficult to analyze. Many of these organizations may have direct ties to states, and some even receive funding from them. Furthermore, some non-state actors have standing in international organizations and can engage in public-private partnerships. To add a layer of complexity we also need to think of some state actors who have agency in peacebuilding. These include autonomous territories, regions and cities that have the ability to contribute to local and regional dialogue, have influence on the shaping of ideas and their implementation, but do not have access to decision making at the international level. And this all goes to show how difficult it can be to ascertain their standing and significance: They lack a formal mandate to act on the international scene. The key elements, however, are that non-state actors do not exercise formal control over a population or territory, although their informal power can be significant and they may, in some instances, step in to fill the government's shoes even without its consent. Political communities below the state make war. This includes substate rival communities, organized armed groups, terrorist organizations. And there's therefore a false dichotomy between these actors and states. But the fact that non-state actors engage in war also means that they must participate in peacebuilding if it is to succeed. And non-state actors can be very effective in peacebuilding and conflict resolution, in part because they have issue expertise stemming from the fact that they focus on very few things, whereas the state must be a jack of all trades. Non-governmental organizations in particular have become increasingly active in mediation and conflict resolution. Their success is sometimes attributed to the fact that they are not bound by the constraints of bureaucracy. They can just gamble a bit more than traditional state actors when entering this field and choose whom they speak to and under what conditions. They are also often perceived as honest brokers and more likely to convey accurate information. In a world where the legitimacy and reputation of actors are a strong source of influence, this is a valuable asset. The lack of focus on non-state actors in international relations reflects the public- private divide that is so entrenched in the field. By addressing this divide, we see a new model of the international order. Feminist scholars have long argued that we need to recognize that the public and private are inherently linked. And by deconstructing the public private dichotomy, we're also able to break down the state/non-state dichotomy. It can therefore be useful to have your gender lenses on when you think about these things. Gender dichotomies in global politics include personal/political, emotional/rational, interdependent/independent, passive/active inside/outside and woman/man as Jean Bethke Elshtain argued in 1988. The public/private is probably the most relevant because we have a tendency to marginalize private spaces where non-state actors also may be more prevalent. The public private divide, therefore, mirrors the division. We expect to be present between state and non-state actors. Things that happen in private spaces, domestic violence and marital rape among them, have so long been treated as private matters and even something that takes place beyond the control or authority of the state, argues Amy Eckert. But certainly this matters in creating peaceful and secure societies. The importance of non-state actors became more recognized in the wake of the terrorist attacks on the U.S., as I said. But that focus was almost exclusively on armed non-state actors. These are important, but we also need to consider other types of such actors who have engaged in peacebuilding much longer than this. I hope this overview has helped you see the reason and the feminist argument that instead of focusing on states alone, we need to focus on a broader array of actors, including those traditionally understood as non-state and therefore outside of the reach of international relations.

4 State and Non-State Actors: Beyond the Dichotomy by Peter Wijninga, Willem Theo Oosterveld, Jan Hendrik Galdiga and Philipp Marten in the Strategic Monitor 2014: Four Strategic Challenges.

Critical Geography of Peace

In this lecture, I will explain the main contributions of critical geography of peace in relation to the crucial importance of space in peacebuilding processes. Critical geography of peace is quite new academic field that has developed in the last two decades and is the result of the crossover between critical geography and peace studies. This field is making very useful contributions to promote analysis and activities in favor of a positive peace, that is a peace based on justice and social transformations. It should be borne in mind that until recently, space had been analyzed in relation to war and geopolitics, but not to peace processes. However, peace processes take place in concrete spaces in a specific geographical context and therefore is necessary to understand the characteristics. Critical geography of space is closely related to a process experienced by peace studies in the new century called Local Turn. It refers to the growing attention paid to all the local dimensions in peace processes, actors, dynamics, cultural interests, etc.. This attention arises from the awareness that the only way to build a peace that is sustainable is one that is accepted by local populations and that corresponds to their needs and desires. Both the local turn and critical geography of peace are based on theoretical perspectives critical of the liberal peace approach, such as the critical theory, or pluralism, feminism and post-colonial studies. The liberal peace approach has dominated international peace and security policies since the end of the Cold War. But it has been questioned, among other things, because it promotes and imposes standardized uniform policies based on Western ideas, such as the state reconstruction, democracy and the free market without taking into account local actors' needs and cultures. These critical perspectives, on the contrary, argue that peace processes should be led by local actors and respond to their interests. However, they also remind us that local factors are closely related to global ones. It should be added that this growing importance given to the local level is a novelty. In it, the local level has traditionally been seen as irrelevant in a globalised world, and both liberalism and Marxism have tended to disqualify it as backward and contrary to development. Political geography of peace has conducted numerous studies and provided very interesting theoretical contributions. First, it shows that space and peacebuilding strongly condition each other. This argument comes from the ideas of critical geography built in the 1970s, which understand space not as something physical, but as a social construction based on social and power relations. And therefore, it is dynamic and changing. Of course, such as Lefebvre and Harvey theorized that space is constructed by social relations, class, gender, race, etc., and that at the same time, space contributes to the construction of society. So, for example, the capitalist system has created the spatial structures with great socio-economic imbalances globally between north and south, but also at the local scale with discriminated neighborhoods in large cities. Applying this vision, political geography of Peace argues that space conditions peace processes, how they are implemented, how resources are managed and so on. But at the same time, as we'll see later, peace processes should be seen as processes of transformation of space. Secondly, critical geography of peace hasn't generated a lot of situated knowledge, that is, it has provided many case studies to explain how peace is built in specific places. These studies help us to understand that there is a great majority of situations on the ground, for example, in many context of armed conflict, there are places that are islands of peace with local peace initiatives, while in countries where there is no war, or the war has ended, there are high levels of violence. This provides a more complex view of the relationship between war and peace and helps to overcome the binary dichotomy between war and peace as complete opposites and the idea that there is a linear transition from war to peace. Thirdly, these analyses have contributed to a more complex understanding of peacebuilding as a social construction. They have helped to see peace not as a final result as something idealized or utopian, but as an ongoing process that is constructed through negotiation, as the fruit of our relations that exist in a given space between different actors who confront different social and political projects, and who even have opposed concepts of peace. A fourth contribution of critical geography of peace is that it pays greater attention to the importance of discourses on space in peace processes. Space is not only a social construction but also a mental construction with perceived space. We imagine it, and attribute to it our subjective, emotional, cultural dimension, sometimes linked to our own identity. As critical geographers say, when we attribute these symbolic meanings to a space, we turn it into a place which is an interesting concept they use, in that some places have a strong symbolic meaning for certain groups who associate them with repression, with their struggles, with their identity, etc.. It is therefore important to analyze the symbolic meaning and use it in favor of peace and coexistence. Some interesting studies in this regard have focused on the Mostar bridge destroyed during the war in Bosnia-Herzegovina and then rebuilt or Tahrir Square in Cairo, a symbol of protest movements. A last contribution of critical geography of peace lies in its normative orientation. Its aim is to build a lasting peace with social justice. And to this end, it proposes a transformation of space to dismantle the geographies of war; the structure of a space generated by conflict, based on territorial domination, violence, and exploitation, and to build geographies of peace; that is forms of organization of space based on peaceful and just relations, reducing inequalities between social groups and territories.

Spaces of Peace by Annika Björkdahl & Stefanie Kappler (2021) in The Oxford Handbook of Peacebuilding, Statebuilding and Peace Formation, Oliver P. Richmond and Gëzim Visoka, eds. Oxford University Press.

Geography and Peace by Nick Megoran, Fiona McConnell and Philippa Williams (2016) in The Palgrave Handbook of Disciplinary and Regional Approaches to Peace, Oliver P. Richmond, Sandra Pogodda and Jasmin Ramović, eds. Palgrave Macmillan.

The Concept of Gender and Gender Roles during Conflicts

Welcome to the module on the concept of gender and gender roles during conflicts. In this module, we want to introduce you to the concept of gender and why it matters for understanding war, conflict and peace. We will present you the main findings of the literature on gender and conflicts, notably related to how gender roles and identities evolved during conflict and post-conflict periods. We will also explore how women and men are traditionally perceived in conflict contexts, as well as in policy and academic research. This will allow us to better understand how gender roles are mobilized for specific types of femininities and masculinities and what it means to trespass these roles. Finally, we will explore how violent conflicts produce different kinds of gendered vulnerabilites. For instance, taking the shape of wartime sexual violence. Besides me, the teachers in this module, are doctor Guðrún Sif Friðriksdóttir who will tell you about post-conflict masculinities in Burundi? And Dr. Itziar Mujika Chao, with whom we will discuss the lack of a gender perspective in conventional international relations and peace and conflict studies, as well as what feminist interventions can bring to the field. We hope you enjoy the lessons in this module, so let's get started.

Gender and Conflict

Gender is a very disputed concept, traditional definitions of gender usually related to learn differences between men and women, as well as to masculinities and femininities, which do not always correlate to men and women, respectively. On the other hand, sex relates to biological bodily differences. Recently, gender studies have progressed beyond the male - female binary and advocate for and all genders approach. This means that our understanding of gender should not simply rely on a distinction between men and women, but also pay attention to gender and sexual minorities. Another point that is important to remember is that gender differences are not static. They vary across cultures and within cultures according to class, age, caste, religion and so on. They also evolve over time. It is therefore impossible to talk about, for instance, women in general and any discussion about gender has to be contextualized. In most of popular and political discourses about gender, there is a confusion that is made between gender and woman. In fact, what it is to be a woman cannot be understood in any given society and at any given moment without understanding what it is to be a man at the same time and place and vice versa. In addition, many researchers in gender studies argue that what matters is not so much whether one is a woman or a man or another gender, but the kind of gender roles and models that one enacts. For instance, a woman can act in a very masculine way and still be viewed as a woman, and a man can act in a very feminine way and still be viewed as a man. Also, most people will behave in a more masculine or feminine way depending on the circumstances. So how and why does it matter when studying conflicts and violence? Well, most of the literature published in conventional peace and conflict studies, as well as in conventional international relations studies, is gender blind. It usually assumes that only men are involved in conflicts or don't mention gender at all. When gender is taken into account, most of the literature presents a rather simplistic view of the gendered impact of conflicts, which can be summarized as follows. Men fight and women are victims in particular of sexual violence. However, over the past decades, an increasing number of scholars, in particular in the field of feminist peace research and feminist peace security studies have started researching gender related issues such as female combatants, female child soldiers, gender based violence in conflicts and so on. We can identify some of the main findings of that literature. For instance, first, there is a relative consistency of gender roles in conflicts all over the world. With a minority of recognized female combatants. Though disproportion varies, there are very few female combatants in national conventional armies around five percent. But they can be a lot more numerous in non-state armed groups, sometimes up to 40 percent of combatants. Another finding is that all around the world, the image of combatants is linked to a specific ideal type of masculinity, which is captured by the concept of militarized masculinity. It means that the masculinity of many male soldiers changes with military training, giving birth to a specific masculine identity. This identity relies on specific attitudes and values such as physical strength, willingness to use violence, but also to sacrifice oneself and the importance of weapons. In practice, however, not all combatants fit that model. Third, feminist literature has shown that gender divisions and gender stereotypes can be understood as one of the basis of structural, physical and cultural violence everywhere in the world. Femininity is usually associated with passivity and weaknesses, and this justifies the political, economic and cultural exclusion of individuals who are judged as not masculine enough. It is also used to justify discriminatory practices and, of course, gender based and sexual violence. In all these processes, the concept of hegemonic masculinity is crucial. Hegemonic masculinity embodies the more honored way of being a man, and only a minority of men might enact it. It varies across time and cultures, but in all cases it legitimizes the global subordination of women to men. Feminist literature has also shown that violence in conflicts is legitimized by a highly gendered language and highly gendered stereotypes. For instance, the discursive feminization of enemies. The dichotomisation of sexes is a way of creating in groups and out groups as the enemies are feminised and the defenders of the community, groups or nation are, on the contrary, masculinist. Finally, feminist research in the field of political economy has shown that the economy of war is largely dependent upon the exploitation of women's labor, notably within armed groups. It has also demonstrated that there is a link between gender inequality, underdevelopment and conflict. In other words, the more societies gender equal, the more developed and peaceful it is. This theoretical advances have been crucial to prove the importance of adopting a gender approach when studying peace and conflict processes. However, there are still many limits to the research that is produced, and much progress still has to be made. For instance, the confusion between gender studies and women's studies lingers in spite of the fact that most of us agree that the two types of studies are largely different. This means that issues affecting other genders are often ignored, overlooked or assumed to be anecdotal. For instance, this is still the case of wartime sexual violence against boys, men or sexual and gender minorities. One of the consequences of these limits is that the interface between research and policy is very difficult to build. Policy makers tend to interpret research results as a call for introducing quotas for women and to think that they have ticked the gender box when they have recruited or invited women. For instance, it's important to understand that gender in peace processes cannot be done by involving women alone of agendas have to be taken into account and attention has to be paid to gender roles and models. More generally, what matters most is to address the way masculinity is and femininity are defined during conflicts as these are at the roots of many forms of violence. End of transcript. Skip to the start.

Women, gender and conflict: making the connections by Martha Thompson in Development in Practice 16. 3-4 (2006): 342-353.

Gender Identities During Conflict

Gender roles and identities evolved significantly before, during and after violent conflicts, for instance, right before, but also during and after violent conflicts, we witnessed an exacerbation of masculine values and in particular of militarized masculinities. This is accompanied by valorization of men during the conflict, as well as by your celebration of war masculine heroes during and after the war. In parallel, women often serve on the grounds on which to persuade men to exert their masculinity and to vanquish the enemy. The idea is that women and children have to be protected by men against the enemy because they are considered as more vulnerable and as less likely to be able to defend themselves. In particular, the stress is put on the fact that women can suffer rape, torture or death during war, giving the male soldier a special duty to protect women from such consequences. This means that popular and political narratives around gender roles and identities during violent conflicts are rather simplistic. The stories that men fight and that women are likely to be victims. In fact, all genders are victims and all genders fight. As we have seen in the previous video the military relies on the construction of soldiers and specifically masculinities terms. While women have always been part of the military, their presence has been systematically marginalized. In conventional armies their role has typically been camp followers, that is, service and maintenance workers, rather than those involved in active combat. They can work as cooks, nurses, secretaries, cleaners and so on. In non-state armed groups, the situation is often quite different, and women have often taken up combatant positions as well. For instance, during the wars in Eritrea, El Salvador, Sierra Leone or more recently in Ukraine, sometimes they are kidnapped and forcefully involved at a very young age, this means that depending on the conflict area, young girls make up from 10 to 34 percent of child soldiers. But beyond the potential involvement in armed groups, violent conflict can have a deep impact on women's identities and roles. For instance, in families where men have gone to fight, women become heads of families, and that entails new economic and social responsibilities for them, as well as considerably more work. They have to deal with the consequences of violence at the local level, for instance, in terms of everyday security, of access to water and food or the destruction of local facilities and so on. These new tasks can be empowering because they take women away from the ideals of submissive womanhood. But at the same time, the conflict period also exposes them to higher risks, for instance, of rape, of forced recruitment, or of sexual trafficking. That being said, feminist scholars have cautioned us against interpreting these higher risks for women as specifically related to the period of violent conflict. Instead, feminist scholars have developed the notion of continuum of violence. Which draws connections across different forms of violence perpetrated before, during and after conflicts. In particular, feminist literature has shown that forms of violence exerted against women during conflicts can be related more broadly to gendered power structures and in particular to patriarchy, which existed before the beginning of the violent conflict. So it is important to understand that women do not face new but amplified risks during conflicts. In parallel men's roles and identities change, too. In order to understand how we have to differentiate between those who take up arms and those who don't. In general, civilian men are likely to be disempowered by the violent conflict because the resources that they used to have or control are no longer available or accessible. This is, for instance, the case of their job, but also the land they owned or the cattle. Their sources of wealth and power have disappeared, and the communities to which they used to belong are often scattered or decimated. Generally speaking, we can say that violent conflicts disempower civilian men as breadwinners and providers because they have fewer opportunities for obtaining an income. In addition, men who don't take up arms and even most of those who do are also unable to protect their families. It means that they are unable to perform an important task related to their masculinity. Patriarchal norms underpinning gender identity are at the heart of the problem because they aggravate men's sense of failure and frustration. The figure of the ideal man as a strong fighter and protector, never defeated and never giving up, a figure of authority and of leadership is impossible to perform during violent conflicts for men who don't or can't take up arms. In addition, poverty distorts gender identity because men are then unable to provide for the household. This can result in various forms of violence as a means of maintaining control and power because as research has shown,violence and aggression are one easy way to reassert masculinity. At the same time, men who do take up arms are empowered by the weapons they hold, but they are also at great risk because of the circulation of weapons. Because each side in conflict associates men with wealth and power, men are the main targets for killing, but also for torture and imprisonment during violent conflict. This means that the consequences of violent conflict on men's rules and status are extremely paradoxical, like what happens for women. It is also important not to forget other genders. We know that sexual and gender minorities are particularly at risk during violent conflicts. In a context where very specific types of masculinity and femininity are valued, they are generally seen as cultural and societal threats by all militarized actors. Little research, unfortunately, has been done on how violent conflict impacts the identities and rules of gender and sexual minorities, but we know that they face higher threats of all forms of violence and in particular of sexual violence, of trafficking and of forced displacement. In terms of gender relations, it is worth noting that the frustrations and trauma generated by violent conflict for all genders may be channeled into aggressiveness in values and highly destructive forms. This can give birth to destructive behavior for all genders, but especially amongst men. In particular, we can often witness during and after violent conflicts, high rates of alcoholism, depression, suicide and suicidal thoughts, domestic violence, abandonment of spouse and children and so on. All of this contributes to further family breakdown and further violent reactions, feeding a cycle of violence that lingers long after the end of the conflict. So to summarize, research has shown that when it comes to gender identities and roles during violent conflicts, there are two parallel processes at play. On the one hand, violent conflict makes it more complicated for all genders to enact traditional models of masculinity and femininity. But on the other hand, new or alternative gender models are emerging or strengthened, such as the militarised masculinity model.

Changing gender role: Women’s livelihoods, conflict and post-conflict security in Nepal, by Luna KC, Gemma Van Der Haar, and Dorothea Hilhorst in the Journal of Asian Security and International Affairs 4.2 (2017): 175-195.

The article examines how the Maoist conflict in Nepal affected women ex-combatants and non-combatants, looking at shifts in gender roles during and after the conflict particularly from the standpoint of current livelihood challenges. The article also considers how women experience state and non-state responses meant to improve their livelihoods security in the post-conflict setting.

Gender and Vulnerabilities

Gender based and sexual violence during conflicts are not a new phenomenon. They have existed for as long as there has been war, but the work undertaken by feminists since the 1990s has contributed to place these issues at the top of the international agenda. All violent conflicts are also characterized by high rates of gender based violence. We can define gender based violence as a violence that targets individuals because of their sex or their sexually constructed gender roles. Gender based violence includes, but is not limited to, various forms of sexual violence. It is important to underscore the fact that all genders and not just women can be victims of gender based violence and of wartime sexual violence. Of course, sexual violence constitutes the most well known type of wartime gender based violence, but it displays different characteristics for different genders. For instance, women are more likely to be raped, forcefully impregnated or used as sexual slaves. They are also more likely to be victims of other forms of gender based violence, such as forced displacement and kidnapping. In order to understand how and why sexual violence against women occurs during wartime, it is important to remember the concept of continuum of violence that I mentioned in the previous video. In many societies, even in peacetime, gender roles and norms, marginalized women, politically and legally condone violence in the family and permit discrimination against women and girls in various spheres. These rules and norms create an environment where violence is likely to disproportionately affect women when conflicts escalate. In that sense, wartime sexual violence against women reflects the patriarchal structure of society, where the women, the female body is seen as the territory to be owned and controlled by some men. In other words, wartime gender based violence and wartime sexual violence take their roots in patriarchal norms and masculine domination that exist in peace times. For instance, rape is particularly effective as a way to assert men's domination because of the concepts of honor and shame that are attached to women's bodies in peacetime. It is therefore possible to say that female rape is as much a form of communication between men, then it is a way for men to exert the domination of women's bodies. According to the so-called weapon of war theory, rape against women is used as an instrument of terror,a war strategy and an ethnic cleansing tool. Women from the other ethnic group are specifically targeted for being raped and their genital organs destroyed. Women, thus cannot procreate anymore or carry children from the other ethnic group. But it is also important to mention that rape can result from opportunistic behavior by soldiers. Soldiers can rape for a variety of reasons, for instance, because of a lack of discipline or because sanctions against such behavior are rarely implemented by military officers, in spite of the fact that most armed groups and armies forbid sexual violence. And these acts have heavy and long term consequences, they generate problems associated with sexual and reproductive health like fistulas, for instance, they also result in unwanted pregnancies, sexually transmitted diseases and HIV infections, mental health problems such as depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress disorder, among many of the consequences. In parallel and contrary to common representations, men and boys are also victims of gender based and sexual violence. Men are more likely than women to be victims of non-sexual forms of gender based violence. In particular, they are more likely to be bluntly killed. It is estimated that men make up more than 80 percent of conflict casualties worldwide, and they are also more likely to be maimed and injured. We also know that sexual violence against men and boys exists, but we don't know exactly to what extent because male survivors of sexual violence are even less likely than women to report those acts. It is therefore extremely difficult to document because of a combination of shame, confusion, guilt, fear, but also stigma. It is, however, estimated that men and boys make up around a third of all victims of conflict related sexual violence worldwide. Of course, wartime sexual violence against men is less talked about than wartime sexual violence against women, but it is still very important because it entails a symbolic appropriation of the masculinity of the other group. It is a proof, quote unquote, not only that the victim is a lesser man, but also that his ethnicity is a lesser ethnicity. In other words, perpetrating sexual violence on men is a way to assert domination over them and to ensure their submission. This is also why sexual torture in detention so often used, for instance, in the well-known cases of Abu Ghraib and Guantanamo. Male survivors have the feeling of having been turned into victims, which is incompatible with masculinity. The man should have been able to prevent himself from being attacked and he should have been able to take it like a man. Many male survivors also fear of being accused of homosexuality, which is in many societies strongly socially stigmatized. And it is even a criminal offence in some countries like Burundi or Uganda. Violated men are seen as unable to protect themselves, so they won't be able to protect their women and their community. Sexual violence against men means not only the empowerment and the enhenced masculinization of the offender, but it also means the dis- empowerment of the individual victim and more generally of his family and community. And since men and male power constitute the backbone of patriarchal societies, that is of most societies around the world, sexual violence against men is a way to create a feeling of vulnerability and disempowerment of the community via the subjugation of its members. Many post-conflict societies find it difficult to accept the existence of sexual violence against men. Because of gender stereotyping, men cannot be victims, they can only be perpetrators. There is also an inconsistency between masculinity and victimhood. The feminization of male victims is sometimes reinforced through the view that only women can be raped. And also, it's important to recall that international support programs for victims of sexual violence target women only or women primarily, and therefore it reinforces the equation that is made between victims and women, thereby excluding male victims or confirming their feeling that they have been turned into women. When talking about gender vulnerabilities in conflict, it is also important to remember that sexual and gender minorities are likely to be particularly vulnerable and targeted for all sorts of violence. These individuals are often forced to hide their gender or sexual identity. If it becomes known they are likely to face discrimination, homophobia, as well as various types of abuse, like harassment, bullying as well as sexual violence. End of transcript. Skip to the start.

I have to speak: Voices of Female Ex-Combatants from Aceh, Burundi, Mindanao and Nepal

Gender in Conventional IR

Gender analysis have been traditionally unseen and sidelined in international relations and also in peace and conflict studies. It is true that feminist perspectives have had a presence in both Although we could say in general that they are still in the margins, like to say, continuously cracking the margins. Feminist perspectives started to gain importance in IR since the 80s and gained quantitative importance through the 90s, especially in peace and conflict studies with the fall of communism and the wars in the former Yugoslavia and Rwanda, and also shortly after the effects of 9/11. One of the initial contributions here is the key question, which is still today Central. Where are the women? Cynthia Enloe posed this question later accompanying it With a need of a feminist curiosity, both when we look at the functioning of international relations, but also when we look at conflicts. Since then, the focus has changed from women to gender to the centrality of feminist perspectives as well. I think it's important to mention these three categories. First, to look at where women are because such a picture, this gives clues about the gender based power dynamics of what is going on. But we also need to look at gender as a power relation and as a category of analysis in order to look not only to women as a homogenous group in any society, but to identify women as an heterogeneous group that might function according to different gender based power relations as well. And of course, gender means also looking at men or any other gender dissidences. How do they move under gender-based power structures? How do they function under these structures? Do they reproduce them? And if they do, how? Looking at gender also means dismantling the binaries that sustain it as well, hegemonic femininities and masculinities, women and men, peaceful and violent, emotional and rational and so on. This bring us to see that in between these dichotomies, there are different gender identities which are also affected by gender based power structures and how such structures tell us different gender identities need to function. Here, of course, a queer lens pushes us to new limits as well. Now, of course, this means questioning all previous central assumptions within IR and peace and conflict studies, because until the arrival of feminist researchers, gender was unseen and therefore international politics, conflicts and wars, peace was understood to be gender neutral. As I was saying, feminist perspectives and contributions make a radical questioning of what has been previously identified as central regarding key concepts, processes or actors for example. If we look at the states, the military security, violence, diplomacy, for example, which has been key for traditional IR we clearly see that they have all been understood through a male or masculine gaze and function as such. We see this, for example, in relation to how we have traditionally understood wars and therefore how we respond to them or what we understand as peace or development. Here, one of the main ideas is that women are different or dissident's gender identities experience differently processes such as conflicts, wars or peacebuilding, for example. These experiences have not been taken into account because those that were masculine experiences were understood as gender neutral and as the only experience. This also means, for example, identifying other international or local actors as such in a context where states have been identified as main actors and relations between states as main dynamics in IR. Women and dissident identities, everyday life or care work, for example. Of course, this means turning upside down the gender binaries through which international relations and politics are understood and analyzed and also function upon. This has also meant to deconstruct traditional gender roles, for example, which means that women do not necessarily need to be pacific or more peaceful, caring or emotional, and that men also dissent to join militaries or women also participate in conflicts as combatants. An idea that I think we need to acknowledge here is also the feminist contributions are grounded in feminist grassroots activism, which means that all these contributions at the academic or theoretical levels emanate from the ground and everyday experiences and activism. So there is a continuous conversation in between the theory on the ground that activism and that, I believe, is one of the key values of feminist perspectives in IR and especially in peace and conflict studies. Researchers within feminist peace studies and feminist security studies have done several contributions, and we can't name them all right here right now, but I think some key issues are the following. The dismantling of the erroneous understanding of women and gender as synonyms, which has been continuously done. Women and gender are not synonyms, first of all, and applying a gender perspective, is not adding women And stirring, or at least it should not be. And having a gender perspective does not mean per se having a critical, having a critical feminist perspective either. Also, when we refer to women, we're not speaking about a woman or women as an homogeneous group. the idea of women being heterogeneous, sharing commonalities, yes, but also full of differences, sometimes even exerting a specific power relations, is what enriches the analysis. For me another important point here is how critical feminist perspectives have brought the focus to the ground or the grassroots and to the everyday. What happens in daily life? What happens in those communities in which no one has paid attention before? What happens in those arenas in which no attention has been directed? And here it has been key also to look at the private sphere, as well as to how the public sphere functions upon the private sphere, or how these everyday life is also part of international relations and politics, and how, of course, part of wars and peace building farther than the most spectacular images or happenings in which they have traditionally focused on. This also bring us to the idea of the continuum of violence which Cynthia Cockburn coined. Violence is not something sporadic spectacular out of the normal as it has been traditionally identified looking at armed conflicts and wars.Violence is continuously present in the everyday and is part of all spaces of life here the most important idea in relation to conflict and peace is that peace does not start when the violence stops and vice versa. Which peace and whose peace starts? And which violence and whose violence apparently ends? The example of violence against women or gender based violence, for example,allow us to see how it is a continuous element both in peace and conflict and how it takes different forms - or not- under different political context and spaces. For me, it's key also the linkage that has been done by feminists in relation to militarism and war and how gender in itself feeds militarism and is a cause for militarization and war. Another key idea here can also be the critique that feminists have directed to the overall actuation of international organisms. These actors have had have usually a central role in post-conflict and peacebuilding, and they tend to be among others. Of course, those who direct the official processes. It's true that such organisms have taken a more sensitive gender perspective or that are increasingly taking women into account. We can see this, for example, with the adoption of the United Nations Security Council resolution, Thirteen, twenty five and the whole women peace and security agenda. However, what do these measures bring? So, for example, they do refer to the participation and protection of women, but of what kind, where and by whom? Here one of the main critique has been that the resolutions have those elements of the sources that they emanate from. That is the United Nations Security Council a nmasculine androcentric and liberals space in itself.

Militarized Masculinities